DURING SAN JOSE GIANTS home games, the door to Buzz Hardy’s Municipal Stadium office doubles as the front of a booth for Heineken beer sales. And although Hardy could reach over and snag some brew at any point during his long work days, his friends take to the tap more than he does.

Still, it’s this kind of casual setup that defines Hardy’s brand of baseball.

“For me, it’s about havin’ a keg of beer in your office,” says Hardy, assistant general manager of the minor-league Giants, taking a break from last-minute preparations for a recent match-up against the Modesto Athletics. “For the fans, it’s a difference between, do you want to go see Barry Bonds, or do you want to see a baseball game? We’re not trying to kid anybody. This is a baseball game; our team’s either gonna win or lose.”

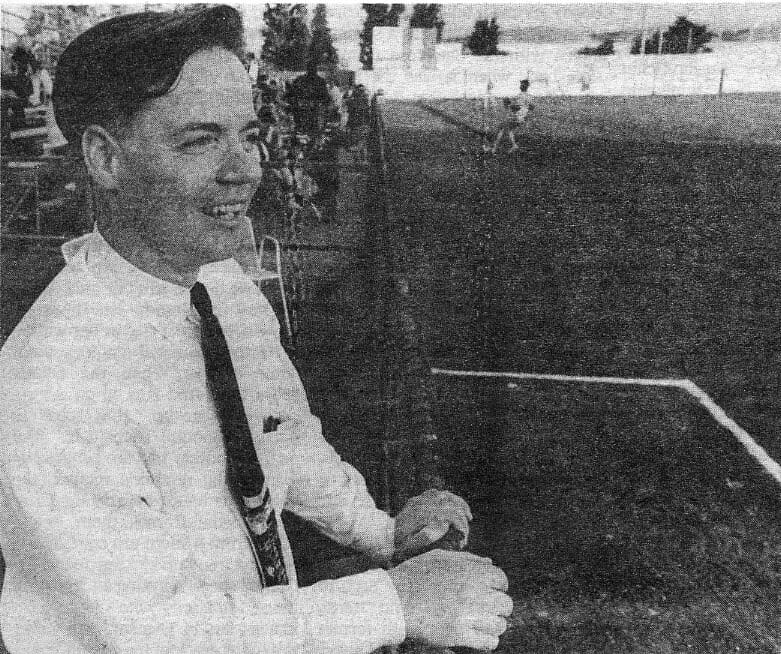

Hardy sports a coating of professionalism, but not so much that he’s slick to the touch, In a painted-cinderblock office with nearly opaque windows, Hardy’s dirty jersey from a Willow Glen High School alumni game is draped across the back of his chair. Pennants and San Francisco Giants jackets adorn the walls, and tiny black San Jose Giants bats hang under the front lip of the desk. Hardy displays signed baseball bats on an angled shelf and autographed balls enclosed within glass boxes, but says he doesn’t care what they’re worth on the market.

The longer this 28-year-old with a Saturday Evening Post face stays with the Giants, the less interest he professes in moving over to the Big leagues, which he once idolized but now views as soulless and over marketed, In the majors, he says, the paramount importance of cash is reflected in inflated player salaries and equally atmospheric admission and concession prices.

Hardy’s job is one part long-range vision and three parts daily sweat. During the busy off-season he sells ads and puts together the slick $2.75 souvenir program book. For the games, Hardy runs the barbecue pit, coordinates the first pitch, takes anthem singers to the field and assembles the lucky number prizes.

Tonight, dressed in a short-sleeve white shirt, button vest and brown pants, he scuttles up to the VIP deck, where season-ticket holders gulp free beer, wine and soda before the game. It’s a typical emergency – the refrigeration unit is shot and the beer is warm.

Then he looks through his prize packets, pulling out a San Jose Giants cap, tix to the Winchester Mystery House, a certificate for a free oil lube and filter. Hardy, who says he still gets chills from a well-sung “Star-Spangled Banner,” untangles the wires for his portable CD player as he finishes assembling a list of songs for the game, from “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” by Frank Sinatra to “No Woman No Cry” by Bob Marley.

“I can formulate in my mind what I need – a form, a compilation of things – and he’ll go and create it,” says Hardy’s mentor, team President Harry Stavrenos. “He’s got a very easygoing personality – sometimes, I think maybe too easy. Some people take advantage of Buzz because he’s too nice, but that’s a good trait.”

“He’s laidback, chic, sassy, confident, organized – a computer wizard,” says Gary Weckwerth, general manager for the Sioux Falls Canaries, a minor league team which the Giants own. “He’s a fun guy to be around. He doesn’t seem to be one who’s afraid of taking risks.”

Hardy started playing Wiffle Ball at age 6 in his back yard, where a tall fence from center to right field suited him well – he batted left. He took a swing at Little League at 8 and became a baseball junkie, keeping extensive stats for ten to 20 teams in his own dice baseball game and announcing the play-by-play when nobody was listening.

“I probably had about a year and a half where I wore a hat every day,” he confesses. “It was hard for my mom to get me to take a shower.”

A Willow Glen High School ball player who didn’t make the team at California State University, Chico, Hardy cleaned toilets and cleared trash out of the stands as a summer intern with the San Jose team in 1985, back when it was the struggling, independent San Jose Bees. Founded in 1947, the team signed its own players from 1984 to 87 until changing its name and becoming affiliated with the major-league San Francisco Giants in 1988.

In the years following his initial internship, Hardy was a scorekeeper, and after his 1990 graduation with a bachelor’s degree in broadcasting he started selling ads for the Giants.

Even though Hardy had no restaurant or management experience, he slid into a spot running the barbecue, initially burning a slew of ribs and chicken. Eventually he moved into public relations, convinced the organization to buy some Macintosh computers, and scored his current title.

He says he was “wide-eyed” about every player when he started as an intern. But now they play Sega or quaff beers together. And Hardy has taken road trips with former San Jose Giants who are now heavy hitters, watching them punch each other and make wisecracks.

Still, the outdoorsman and basketball fan adds, “You only trust them so much – they’re not your best greatest friends but somebody you can hang out with and not talk about baseball with, just talk about life or whatever.”

His all-time favorite player in the majors is former San Francisco Giants man Willie McCovey: “He had that swing that was so menacing, so imposing, yet he was like the most gentle guy to the whole world.”

On one recent evening, the Giants are trying to menace the Modesto A’s, top-ranked in the six-team Northern California division. Cowbells are clanging among the small home audience, which responds to bad calls with boos that sound like the tolling of a lighthouse. It’s a familial, witty bunch; when one man complains that the tardy scoreboard still shows only two strikes for the Giants even though the A’s fielders are leaving the greens, another fan yells from halfway across the stadium, “It’s bargain night.”

Between a few of the innings, Hardy organizes prize contests on the field. In some of the games, fans try to launch a baseball through a hole to a Pepsi sign and players attempt to hurl a ball into the headlights of a car. In another diversion, Hardy races a fan to home base. He does a kind of duck walk, his vest flapping; he lets the woman win, her shirt tied at her waist.

Hardy’s musical choices elicit some smiles: When the Giants score their first run off an A’s infielder screwup, the speakers blast, “Whoomp! There It Is.” And as the Modesto players congregate around the pitcher’s mound, the vaudeville bounce of the My Three Sons theme frames them like a scene from a silent-era comedy.

The A’s end up kicking dirt on the Giants’ shoes, winning 2-1 in ten innings. But Hardy, who’s marrying a Braves fan in October, will never tire of the crack of the Giants’ bats.

Hardy pines for the days when baseball was more than just a game. He adores the film The Natural because it embodies baseball nostalgia, with fans attending games in suits, ties, hats and dresses.

“It was kind of a way of life,” he says, “and for the people that followed it, it was like a life-or-death thing.”