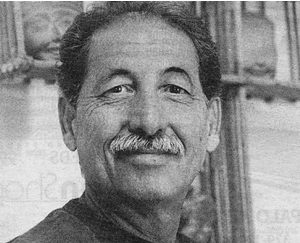

ALTHOUGH HE helped change American society through the Chicano movement, Tino Esparza doesn’t proclaim himself a hero. Rather, he reverently narrates from memory the names of the students and community activists he’s worked with on each landmark struggle.

“I feel a lot of pride that I had a hand in doing something.” says the 58-year-old organizer with sad eyes and a sincere smile. “My involvement is an extension of who I am. Growing up in the San Joaquin Valley with really terrible poverty conditions, I could relate to a lot of different people.

“And in my life I’ve always had some kind of help,” says Esparza, who was recently diagnosed with incurable brain and lung cancer.

As a boy, Esparza and his family – including half-brother and now-San Jose city councilmember George Shirakawa – were placed in a World War II Japanese internment camp. The boys were released when their mother intervened through a congressman, but the experience forged their activism against injustice.

After transferring from San Jose City College to San Jose State University, he and Chicano student activists hatched a plan to take on higher education, first organizing walkouts at local high schools.

In 1968 he brought Cesar Chavez to campus to kick off the activists’ campaign for increasing the number of Chicano students at SJSU. Esparza gathered Chicanos from around the state to attend graduation in Spartan Stadium, where they all walked out at a prearranged signal. Then, at the track field, they held the nation’s first Chicano commencement.

After that, he helped persuade SJSU to create the nation’s first Chicano studies graduate program. “It was a magical time, where people didn’t sit back and talk about it, they did something,” says Esparza, who has also helped create support programs at SJCC, advised students at UC-Santa Cruz’s Oakes College and taught Chicano studies at SJSU. “We were all one voice.”

Now he’s pushing for an endowed chair at SJSU in honor of Cesar Chavez and trying to fund a creative-arts program to “take the guns and dope out of the kids’ hands and put an instrument or paintbrush in their hands.”

His mother, a court interpreter, taught him the value of aiding others – though, he says, “you should let people preserve their dignity while you do it.” In this spirit, Esparza’s friends hosted a “Day of Hugs” for him Sunday, August 8, in the SJSU Ballroom.

Esparza, who expects his first grandchild in October, says he plans “to just keep going. There’s more and more and more that needs to be done.”