Mike Demma is loco for locomotives, and his wife Kathy won’t let anyone forget how maddening his madness can be.

“He almost killed us one time,” she says. “We were driving along on our vacation and there were these train tracks…”

“This is all a lie,” Mike interjects playfully.

“No, it isn’t,” she retorts, “because I got about 20 gray hairs on that one. He was driving along all these train tracks, and he sees these little bits of smoke there. And all of a sudden he just goes, Whrrrrr! and turns the car around like that and skids in the gravel and slams on the brakes. The car doesn’t even hardly stop and he’s out runnin’ with his camera.”

Ever so rationally, Mike explains that he hadn’t expected to see a train chugging over that steel bridge in Idaho. “When I saw the diesel smoke I turned around and got back to the bridge.”

“He didn’t say anything,” she complains, “he just cranked the car around!”

“I figured if I’d asked, you’d have said no.”

Kathy laughs amiably with her husband, but she knows what his first love is: a 1923 steam engine called No. 2479. He’s even risked getting squashed by this 280,000-pound lover as he’s helped renovate it at the Santa Clara County Fairgrounds. His locker there is emblazoned with a bright orange sticker that proclaims the word “RAILGEEK.”

“I have to go down to the fairgrounds and bring him his lunch to visit him,” she says. “When a train goes by, that’s all he sees.”

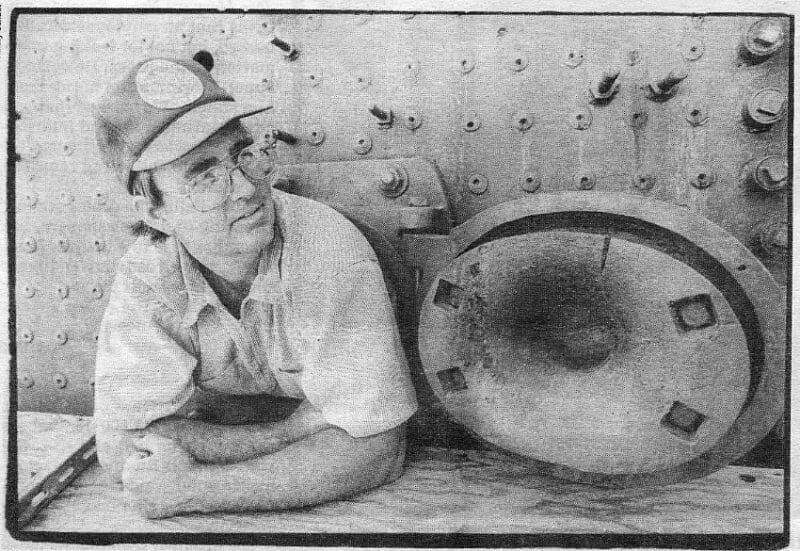

Indeed, the 42-year-old rail buff looks perfectly at home a few days later, shimmying through a hole into No. 2479’s 7-foot-tall firebox. Demma’s voice reverberates as he squats inside and discusses the finer points of steam technology and his zeal for trains.

“When they’re steamed up, they have a life of their own,” the San Jose resident says. “They breathe. There’s a lot of little places where steam leaks from. They hiss and they moan and they bubble and groan. You get dwarfed – it kind of puts you in perspective.”

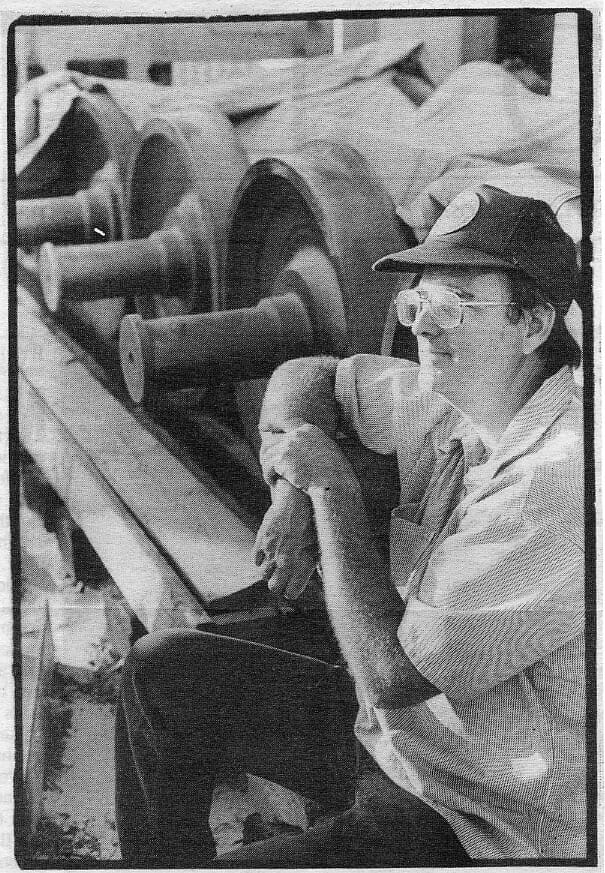

Demma, who is distracted in the weekday hours by a full-time job in commercial refrigeration, sometimes works on No. 2479 two or three times a week along with the 30-40 other core members of the Santa Clara Valley Railroad Association. They’re hoping to restore it to glory by next year, in time for the rededication of the Cahill Station in downtown San Jose.

I Liked Ike: No. 2479 ended its service on the San Jose-San Francisco commuter route and was placed in the fairgrounds in 1957. Photo: Hillary Schalit

Designed to pull passenger trains along routes like the one between Sparks, Nevada, and Salt Lake City, Utah, No. 2479 ended its service on the San Jose-San Francisco commuter route and was placed in the fairgrounds in 1957.

Currently stripped of many of its exterior pumps, heaters and other mechanical goodies for repairs, the engine looks like an “Expert Builder” Lego set left unfinished 30 years ago. Surfaces are covered with rows and rows of bolts. Cryptic numbers and circles are chalked onto the engine’s faded red paint.

Demma says the engine – which could easily reach a maximum speed of 90-95 mph – fascinates him because it was built with little or none of the technology existing today. The frame, for example, is a one-piece shell casting, while today’s engine skeletons are fabricated out of steel parts and welded together.

“For me, the most rewarding thing is gettin’ a feel for what the maintenance people had to do on a daily basis to keep it running, everyday of their lives, 10-12 hours a day,” he says. “It’s tough physical work.”

Demma, who once filmed the 2479’s renovated sister in action at 70 mph from the back of a speeding pickup truck, eagerly lugs out a bundle of photo albums that capture the 2479’s past and present. “He has more shots of this than his kids,” Kathy Demma notes. “That album is even better than our wedding album.”

One old photo shows the 2479 after an accident in 1937, when it struck a Model A auto lodged on the tracks at 70 mph. The fuel car and seven cars derailed, killing some members of the crew.

Another neatly labeled series of shots illustrates Demma’s most frightening moment with the locomotive, as the team of volunteers pulled the 6-foot-diameter wheels out from beneath the behemoth engine for repairs. With 50-ton pneumatic jacks, they lifted the 80-ton engine onto wood planks and steel I-beams, two inches at a time. Near the apex of the engine’s 52-inch vertical journey, some of the supporting lumber began to crush unevenly and the back end of the engine shifted eight inches, putting himself and the crew in danger of getting flattened.

Some of Demma’s fondest memories of childhood are of sitting on boxes behind his dad’s San Carlos grocery, watching steam engines pull passenger trains. At home he played with a model train set – American Flyers – but when his grandmother moved into the household he had to take it down. When one of his brothers acquired a fondness for cars, the brother tragically sold the whole train set at a flea market to buy auto parts.

Demma re-entered the locomotive world ten years ago when he bought a simple model train set for his kids. As it chugged around the Christmas tree, his interest was rekindled. He moved on to constructing models, but found he didn’t have the dexterity to work with the small parts.

He then started volunteering as a conductor for the Billy Jones Wildcat Railroad, a one-third-scale 1905 steam engine in Vasona Lake County Park. That involvement led to No. 2479 in late 1989. Since then, he’s versed himself in the ways of locomotion through reading railroad publications and pamphlets in antique stores as well as seeking arcane knowledge from other enthusiasts.

Although the group has almost finished restoring the fuel car, Demma is getting antsy.

“We need to finish something to kind of boost morale,” admits Demma, whose wife directs the railroad association’s ongoing fundraising campaign. “We’ve been coming down here for so long, and taking things apart, that everyone has expressed the need to see something be put back together.”

But there is a light at the end of this tunnel: the proud beam from the snout of a creature reborn.

“Because it’s not running and the project is so massive, we go down there a lot of times and look at it and think, ‘Boy, we haven’t really done anything over the last two years.’ But then when you pull out the photographs, you realize you have done quite a bit.”