AFTER STRESS-INDUCED endocrine tumors sent pastor Dick Miller to the hospital for months in 1982, he realized it was time at last to drop his life-long heterosexual facade.

“I was denying myself in order to do ministry,” says Miller, 54. “But I don’t think that’s the kind of self-denial that’s called for in the Christian faith. I think we’re called to be ourselves first.”

Miller came out at age 42 and left a suburban Washington, D.C., ministry. He divorced amicably from his wife and ran a gardening business in San Francisco’s Castro district for five years.

But his vocation called to him. Now Miller, pastor of First Christian Church in downtown San Jose, is the only openly gay pastor in the million-member Disciples of Christ denomination. Last year, he cosponsored the national church’s reaffirmation of support for gay rights.

An introspective and somewhat introverted man, Miller tries to strike a balance between the demands of tending to his flock and to his own emotional well-being. “The ministry for me is not easy,” says Miller, who draws energy from a weekly meditation group at the church. “It’s so demanding, you don’t have any life of your own.”

ALTHOUGH HE was involved in an on-and-off relationship when he lived in the Castro, the workaholic’s hectic schedule has curtailed pursuit of romance. And dealing with members’ problems can be especially exhausting since his “open and affirming” church is a kind of sanctuary for people who’ve had bad experiences in other denominations.

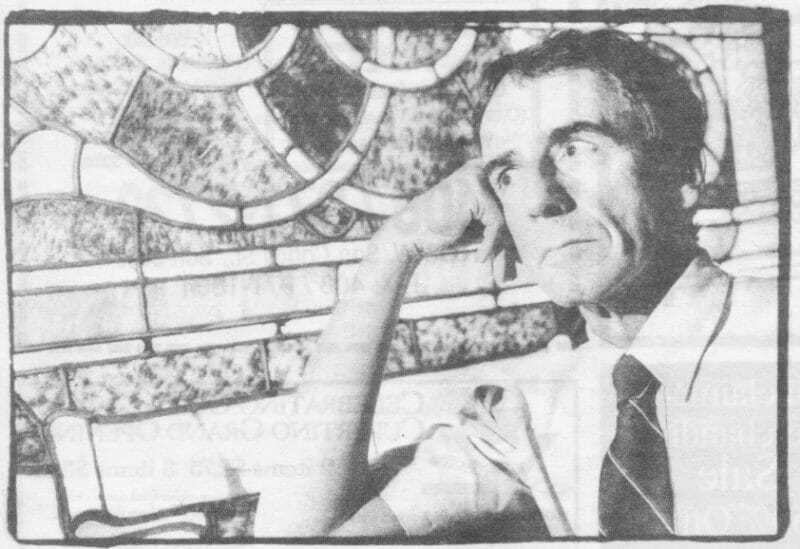

Religious Reformer: Miller urges acceptance of the motto “semper reformanda” – “always reforming.” Photo: Hillary Schalit

Miller, who used to backpack alone during his marriage as a way of dealing with his sexuality, recently returned from a solo four-week hiking trip in the Sierra to heal from a stressful year at the church.

During his vacation, the thin, tanned man didn’t take any books and carried no pen and paper with him for the first couple of weeks; he says he wanted to venture into the wilderness with what he already had in his head.

Hiking up to 16 miles a day, he thought about how to simplify his life and how to quit putting off some important tasks. But mostly he enjoyed not having to worry about an agenda.

Still, omnipresent in his mind is the religious right’s vigorous attacks on gay rights, which he says are rooted in the fear that sexual freedom will destroy patriarchy in this country.

Miller, who points out that none of Jesus’ words in the Gospels address homosexuality, says he is distressed at the religious community’s general move toward almost “fascist, nationalistic” beliefs.

Mainline denominations such as the Methodists and Presbyterians have lost members when trying to deal with real issues, while the rather magical thinking of fundamentalism has appealed to an insecure populace grasping at some kind of certainty, Miller says.

Fundamentalism’s power, he says, lies in its autocratic structure. While mainline churches possess a democratic form of government and a credentialing process for clergy, Miller says many evangelical churches are “little dictatorships” without such academic and theological standards for pastors.

Still, Miller thinks the political power of the loud and well-organized religious right is greatly exaggerated. Fundamentalism could be merely a passing phase, like the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, he says: “There have always been reactionary movements in America, and religion has been used by reactionaries in the past. At the same time, the most prophetic voices in our culture — and globally — have been inspired by religious faith. Religion is a very multifaceted thing.”

As a boy, Miller denied his homosexual feelings because of his very religious family’s homophobia. The Albuquerque native often went to sleep listening to his engineer father singing sacred songs. Both of his grandfathers were ministers, and his two younger brothers also turned to the clergy as adults.

As an undergraduate at the University of New Mexico, the “Great Books” honors program radically challenged Miller’s beliefs and introduced a more critical element into his appraisal of religious ideas. At the Yale Divinity School, the voluminous readings on Christian thought and doctrine didn’t teach him practical tools of pastoral technique, but rather an understanding of the faith’s constant evolution.

Working toward open housing during the civil rights era, Miller says he became disillusioned with the gap between Christianity’s rhetoric and its reality. He learned that in his own Disciples of Christ congregation — one that had held its first meeting in his own living room a decade earlier — people considered him a communist. To Miller, his work for racial justice seemed basic to Christianity.

WHILE PASTOR at a church in Connecticut, he became frustrated with the church’s inability to deal with antiwar protest. And, burned out from involvement in dozens of boards and committees, he quit the ministry and taught English at the University of Maryland for three years. Miller also journeyed to India to study with yoga teachers and to Nepal to tackle Mount Everest, where he realized the “spiritual gifts of humanity as a whole” and broke away from some of his Christian provincialism.

Miller later returned to the ministry, then quit after his coming out, and eventually filled in as pastor at an ailing Disciples of Christ church in Eureka. Two years later, a search committee for San Jose’s First Christian Church caught wind of his success in Eureka. Although there was no nucleus of gay members in San Jose at the time. Miller says the congregation accepted his sexual orientation, seeing it as an issue of justice. Now, a “Gay and Lesbian Affirming Disciples” group meets at the church monthly.

The church – a founding member of the San Jose Urban Ministry, now named Innvision – calls itself a “Shalom” congregation. The Hebrew word means peace for justice and the well-being of the total community. Still, the church doesn’t operate as an “adjunct liberal Democratic club,” Miller says: Republicans are most welcome.

During his tenure, the congregation’s ethnic diversity has increased and its median age has dropped, says Miller, whose 27-year-old son lives in Cleveland. About half of the membership and most of the members of the church board have joined in the last five years. Sunday service attendance averages about 100 out of 160 actively participating members. While the numbers haven’t really increased since before his arrival, Miller says the congregation has gained vitality.

He struggled hard to persuade the local region of 70 Disciples of Christ congregations to pass a statement declaring the churches as being open and welcoming to gay members and pastors. The assembly deferred the statement the first year, and Miller was crushed.

But the next year, after members of his church and a few others visited every congregation to dispense. education about homophobia, the statement passed by more than 90 percent of the vote.

But Miller’s work continues. Several gay and lesbian members of his congregation are ordained and would like to serve as pastors elsewhere but are hitting an invisible barrier of homophobia at area congregations, which vote for their own ministers.

Miller, who met Martin Luther King Jr. a few times and joined the March on Washington, likes to quote from King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which calls for the church to be “not the taillights but the headlights” for social transformation and justice.

Miller’s own “9.5 Theses for a New Reformation” – reduced from King’s famous 95 Theses to appeal to today’s shorter attention span – call for a rediscovery of the “radical tension” between the values of Jesus and of conventional society. They also espouse a reverence to the planet as a living organism, a refusal to worship the flags of nations and an affirmation of the diversity of human sexuality.

In his theses, Miller also urges acceptance of the motto “semper reformanda” – “always reforming” – even though he cannot predict where that reformation will lead American religion in the years ahead.