WITH A SHUFFLE of a curtain, Stan Shaff emerges from a hexagonal portal that looks like a prop from the original Star Trek series. The composer leads his audience through a shadowy, gurgling labyrinth into the round inner sanctum of Audium, a theater of “sound-sculptured space.” He describes the labyrinth as an umbilical cord sending listeners back to the mother’s womb, where sound is one of the first senses that humans develop. In the womb, he says, “We’re recording from before we are born.”

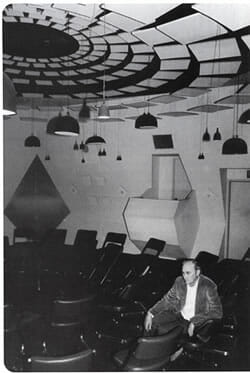

Inside this little-known San Francisco non-profit theater, 169 speakers line the sloping walls, floating floor, and suspended ceiling, forming a hanging mobile in orbit around a massive speaker just a few feet overhead. Some speakers are as small as cucumber halves. Expectant listeners’ silhouettes, seated in concentric circles of chairs, slowly vanish. Shaff envelops audience members in complete darkness to allow them to dwell inside the sounds. “As soon as you’re looking at something, the sound becomes diminished,” he explains.

Seated in an alcove above the audience, Shaff controls each taped sound’s origin, its destination, and its velocity with a complex, custom-designed console that has been his “instrument of space” for more than 30 years. To him, every Audium speaker – from the 18″ woofers to the midrange tweeters – sports a personality. “The structure itself,” he says, “is part of the work.”

The patterns he creates during the live performances are unpredictable. Some synthesized notes are like a ball hitting the ground and slowly coming to rest. Others are aural rubber bands. Notes and rhythms chat with each other overhead, as if the audience members are children gazing up at adults engaged in a conversation they cannot understand. The silicon-based sounds flip to the carbon-based: the summery lull of crickets, the crow of a rooster, and a child imitating the rooster. A prancing marching band and the magical lilt of a far-off train serenade the listeners.

After one hour, the experience ends as it began, with a soft gurgling. The audience emerges from the womb, and Shaff hopes that for at least a few minutes they will reconnect with the sounds in the outside world. One listener says the experience is like “being massaged by sound.”

After one hour, the experience ends as it began, with a soft gurgling. The audience emerges from the womb, and Shaff hopes that for at least a few minutes they will reconnect with the sounds in the outside world. One listener says the experience is like “being massaged by sound.”

Audium’s acoustic sounds are truly compelling. Shaff enthuses about evocative, surreal sounds touching an inner light, a dream world, to form a new language of sound and music. And with people becoming more conscious of surround sound and virtual reality, Shaff thinks they just might be ready at last to appreciate the revolution that’s been taking place at Audium for three decades.

The Audium concept took shape in the late 1950s and early ’60s, when visual artists were taking risks but composers had not yet embraced surrealistic sound. A young brass player and composer at the time, Shaff first toyed with placing musicians at different points in a single location. But he found his pursuit of a new musical vocabulary blocked by the inadequacy of audio technology and performance spaces. Along with equipment designer Doug McEachern, he opened Audium’s first public theater in 1965 and has tried ever since to open people’s ears to space as a counterpart to rhythm and melody.

“Space itself has a compositional potential,” says Shaff, who is now retired from a 30-year career teaching humanities classes on perception and awareness (he considered university music programs too stodgy). “Much of 20th-century music has hinted at the sculptural aspect of music, but I think Audium begins to knock that door down.”

“Space itself has a compositional potential,” says Shaff, who is now retired from a 30-year career teaching humanities classes on perception and awareness (he considered university music programs too stodgy). “Much of 20th-century music has hinted at the sculptural aspect of music, but I think Audium begins to knock that door down.”

With orchestras struggling to maintain audiences, Shaff notes that sitting motionless in front of a symphony hall stage is irrelevant for the 21st century. He points to group sound environments like discos as breaking down barriers: “There’s a willingness to drop the more traditional view of putting a record on and simply letting it go and taking the space and using that sound to shape it in some form.” Shaff heeds the teaching of composer John Cage: Life itself is a sound world. His next work, which he is currently editing, will consist largely of acoustic samples.

He applies Jung’s idea of visual archetypes to the aural, gathering sounds such as bells and gongs that are part of the “sociological sound world we all experience.” He’s also recorded at playgrounds throughout ethnically diverse San Francisco, seeking the melodic, harmonic quality of young children’s voices that transcends languages.

Prevalent in almost all his work are the varied sounds and textures of liquid, which he says connect humans to their evolutionary emergence from the ocean, to an inner vibration, even to the universe itself. “I’m always in search of those feelings,” he says. Shaff exploits the power of sound to stir long dormant memories. When he unwittingly walked past his San Francisco elementary school some 35 years after his graduation, he was jarred by the sound of the bell in the yard. “A whole uncontrollable swarm of memories and feelings emerged,” he marvels. “That bell had everything wrapped up in it — how we waited for recess, where we had experiences even more profound than that in the classroom.”

Shaff hopes to teach listeners that any sound, at the right moment, can be profound – even the sound of a closing door. During college, as an usher at the San Francisco Symphony, he had to enter the hall some time before the audience arrived. He heard a 900-member chorus practicing Beethoven’s Ninth with the symphony, and the director felt something was wrong with the climax.

“The choir hits a very tremendous chord, and then he cuts it off with this total silence,” Shaff recalls. “During that silence, inadvertently someone closed one of the exit doors. It just fractured that moment. When the conductor put down the baton, you knew he was going to explode. But looking back at the 900 people sitting there, he just said, ‘You’ll never hear a more profound door.’

“How many times,” Shaff marvels, “will you hear a door slam after 900 voices reach a climax?”

Successfully exploring that kind of profundity will require a radical new approach in the sound environments of the future. “Maybe we should swing in hammocks,” Shaff ponders, “Maybe we should have a specially designed seat and we spin in it. Or maybe we will wander through it and engage it in a full body way. There are infinite ways to be part of the composition.”

For info, call 415.771.1616 or go to www.audium.org.