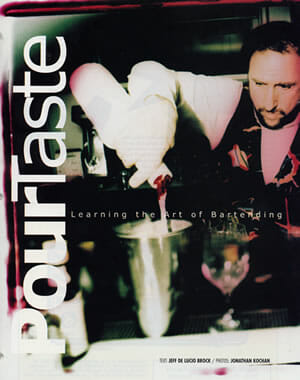

WITH SEVEN STUDENTS stationed behind a half-octagon classroom bar, Ralph Verrone is pouring shots of wisdom as easily as he’s dispensed countless ounces of liquor in his 30 years as a professional bartender.

One morning at San Francisco’s 10-year-old National Bartending School, he’s telling his charges about the contradictions of booze – for example, Blue Curacao is orange flavored, and Sloe Gin is not gin but a liqueur made from berries. He also tosses out tidbits such as the physics of vodka (it doesn’t freeze) and the flavor of Campari (“Nothing tastes like Campari – it only tastes like itself”).

Verrone, who inherited a dry sense of humor from his father Jackie – a standup comedian who voiced the animated Frosty the Snowman – recites the mnemonic devices these twentysomethings will need to succeed behind the bar. For a Golden Dream, which contains Galliano, Triple Sec and orange juice, or GTO, he says: “It’s my Dream to have a GTO car.” For a Rusty Nail, comprised of Scotch and Drambuie, or SAD: “You’d be SAD if you stepped on a Rusty Nail.”

After two weeks of four-hour daily sessions, students learn more than just the difference between the ABC and a BAC. They gain entry into a line of work that can land them more than $20 an hour.

“We’re producing bartenders as opposed to (just) beer pourers,” says co-owner Roger Grimm, who at age 60 is old enough to be the grandfather of most of his students.

For a tuition fee ranging from $395-$595, students learn 140 mixed drinks, selected from the thousands of extant concoctions to illustrate the range of what they’ll be asked for in the real world. They also develop such skills as pouring a shot of exactly one ounce.

This morning, Verrone is showing how the drinks’ placement in the bar follows a standard order, with cheaper, generic booze living down in the well, more expensive brands taking up residence on the wall, and, towering above them all, a penthouse of seven single barrel bourbons.

All labels should face forward, but a good bartender doesn’t need to read them, depending instead upon the bottles’ distinctive features, like Crown Royal’s jewelry-bag slipcase and Galliano’s giraffe-like neck. “I hate to see a busy guy behind the bar saying, ‘Hold on,’ and reading labels,” Verrone says.

One of many handouts illustrates all the glassware, from the diminutive Pony to the stout Snifter and the elegantly curved Tulip. Verrone points out a pair of fuzzy black glass cleaners that look like overgrown Q-Tips; they’ll remove every stain except lipstick, which must be rubbed off with a bar napkin. Student Lauren fills up the “coffee” pot with dark brown water from a bucket underneath the backbar. Other tubs filled with colored water substitute for real booze, while the jugs of “cream” are actually milky-looking water. Because the school is not allowed to use real alcohol, it’s hard to teach layered drinks, since they depend on different fluid densities, Grimm says.

One of many handouts illustrates all the glassware, from the diminutive Pony to the stout Snifter and the elegantly curved Tulip. Verrone points out a pair of fuzzy black glass cleaners that look like overgrown Q-Tips; they’ll remove every stain except lipstick, which must be rubbed off with a bar napkin. Student Lauren fills up the “coffee” pot with dark brown water from a bucket underneath the backbar. Other tubs filled with colored water substitute for real booze, while the jugs of “cream” are actually milky-looking water. Because the school is not allowed to use real alcohol, it’s hard to teach layered drinks, since they depend on different fluid densities, Grimm says.

Verrone calls out orders to drill the students: “I want a whiskey sour, a Tom Collins, and a white wine spritzer.” The students double-check their guide books, and as ice tumbles in stereo around the room, student Kim Fanene sets a row of four glasses before her and begins her handiwork. She then pours some out and starts over.

At first, student Paul McKinney’s glass remains stuck inside the mixing cup like a bear sticking its head inside a tree hole, until Verrone shows him how to hit the cup’s sweet spot. “Give me an Irish coffee without sugar, a wine cooler, and a Stinger,” Verrone requests. The petite Lauren, who looks like she wouldn’t survive five seconds in the rougher bars, drops a glass, which shatters. “I’ve done it a million times,” Verrone consoles her.

When Verrone asks for a Grasshopper – the first drink he ever made as a bartender – the students whip up elixirs that cover the spectrum of green hues, from rich forest to pale lime. But they get in sync with the Pink Lady, producing identical shades of pink.

At the end of the two weeks, students take a one-hour written exam, which requires a passing grade of 85 and covers drink recipes, customer service, regulations and the latest hot products, like small batch whiskeys. Then students have to prepare 12 drinks, three at a time, in less than seven minutes, using the right glassware, contents, varnish and presentation. An optional class called TIPs – Training in Intervention Procedures – expands upon such skills as what to do when your best customer walks in drunk, how to clear out the bar when the clock strikes 2 a.m., and how to recognize ABC stings. “As a bartender you can ask everybody coming into your place, ‘Are you an ABC agent?,’ and if they are, they must say they are,” Grimm reveals.

Grimm has packed a database with 1,000 employers’ names and says he’s never had a serious student fail to find a job: “To have the phone ring and hear someone say, ‘I just got that job,’ that’s really fun.” And very often that job is quite lucrative.

Grimm has packed a database with 1,000 employers’ names and says he’s never had a serious student fail to find a job: “To have the phone ring and hear someone say, ‘I just got that job,’ that’s really fun.” And very often that job is quite lucrative.

“We say it and we mean it, you should expect at least a total of $20 an hour,” Grimm says. “If you’re not doing that, you really ought to find out why. It may be you, it may be the place.” The tips add up: “You go to a bar and order a $3.50 beer. You leave a five down and what comes back? A dollar and a half, right? And a lot of people leave it on the bar. It doesn’t take many of those to get $15 an hour, plus $6 in wages.”

Fresh-faced grads can start raking in the bucks early. At a lavish party in San Francisco’s Richmond District, one recent grad – making mostly Manhattans and Martinis – scored $100 in wages and a $200 tip, and passed out her business card to the 40 Rolls-Royce-and-Porsche-driving moguls attending.

Conflicts with owners or bar managers can raise students’ stress levels, especially if the managers don’t follow through on their financial commitments, Grimm notes. “There’s a place down the street where you can make a lot of money as a bartender but you’ll never be paid one penny of your wages,” Grimm says, frowning. “You make so much in tips that everybody tolerates it.”

Student McKinney – who worked as a waiter for three years and now needs a night job to supplement his daytime acting auditions – is hoping the class can catapult him over the stepladder process he’s seen at restaurants where “you start out as a server, then a barback, then a bartender.” Fanene, a former travel agent, wants to work in a club or a busy bar. So far she’s learned the fine art of social interaction. “You can’t get too involved,” she notes. “Be friendly, but don’t butt into their conversations. Don’t talk about controversial topics.”

Amid all the complex recipes, pouring techniques and myriad glassware, a simple smile is often the hardest skill to teach. “They hear it, they understand it, but I don’t know if you can teach that,” Grimm says. “Some people just are not smilers. If we see somebody who’s really uptight in general, we ask them, ‘Is this something you really want to do?’”