Rowing upstream through the flood forests of Ecuador’s Imuye Creek, with the eerie call of the howler monkeys sounding like the walls of a strong wind, Alex Rubin says he reached a point where it seemed the very fabric of space teemed with life.

“When you’re in the middle of a rain forest and you can sense that almost everything that’s alive is in this 2 percent of the total land mass, it’s mind-boggling,” exults Rubin, founder of the Tropical Rainforest Coalition. “You get a sense of the interconnectedness of everything.”

Intricate relationships bloom in rain forests, like the inch-long, black Peruvian ant which devours the seeds of the tree-hanging itininga vine. As the ant scales the tree it slowly dies, and a new vine sprouts from the dead insect’s belly. The Yagua tribes then use the vine to tie the beams and posts of their stilted houses.

Rubin, 34, will avoid swatting a bee, allowing it to take its pollen to its destination, because he beholds life as an enigmatic jigsaw puzzle. But the rainforest piece is about to fall out. “We’re the last generation that realistically can do anything about it,” he says.

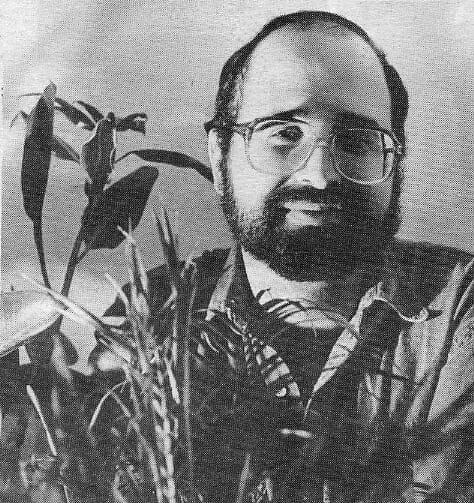

Leafy plants lit from below throw the forest’s shadow on the walls of his pristine Rose Garden home. His lovebird’s piercing call often overpowers the gentle voice of this Madrid native, who grew up in Houston with a love for nature. Now, at NASA’s Ames Research Center, he grapples with questions like the effect of zero-gravity on human physiology.

The South Bay group, which Rubin created after tiring of the detachment of national organizations, aims to convert companies and well-rooted couch potatoes with a soft-sell but uncompromising approach that reflects Rubin’s own personality.

The group eschews protests for more direct techniques, like securing local corporate funding to help an Ecuadorian indigenous group create a forest preserve. It’s also frantically trying to catalogue 10,000 years’ knowledge of rainforest pharmaceuticals. One such elixir, a mixture of palm latex, leaves and vines, quickly healed the wilting arm of a PBS cameraman during an eco-documentary trip to Ecuador.

On that voyage, Rubin was floored by the destruction in the oil town of Coca, where oil-soaked dirt roads spewed nauseating fumes and children trudged on top of pipelines with their feet and hands drenched in crude. Ecuadorian indigenous groups’ serene patience amid such cultural genocide deeply impressed him: “They have a strength in knowing they have a long, tortuous road ahead of them.”