WHEN MARIA VASQUEZ woke up for her first day of classes at Stanford University in 1989, the media robbed her of the carefree honeymoon that new students usually enjoy as they absorb their surroundings.

A note slipped under her door during the night informed her that a producer was interested in making a movie of her life. Her roommate, Cindy, who had just returned from breakfast in the dining hall, warned her that a legion of reporters was waiting downstairs to accost her.

Vasquez skipped breakfast, lunch and dinner to avoid them.

Under the guidance of a university staffer, she later convened a press conference to deal with all the questions at once. A childlike, almost sad Vasquez peered from the front page of the Oct. 2, 1989, Stanford Daily, a row of microphones pointed toward her face. The reporters all wanted to hear the tale of the teenager who had been living with her family in an Oxnard homeless shelter for a year and was now a student at Stanford University.

“I was literally being crushed,” says Vasquez, who was featured later that day as ABC World News Tonight‘s “Person of the Week.” “I was swamped with people who wanted to know so many things about my life. Before that no one cared at all. It was pretty stressful at first. I didn’t want it. But then I decided that it wasn’t a choice whether I wanted the attention or not; it had to be done. What was at stake was more than just my privacy.”

Her story, which came at a time when the issue of homelessness was finally saturating the country’s newspapers, refuted stereotypes of the homeless as unintelligent losers.

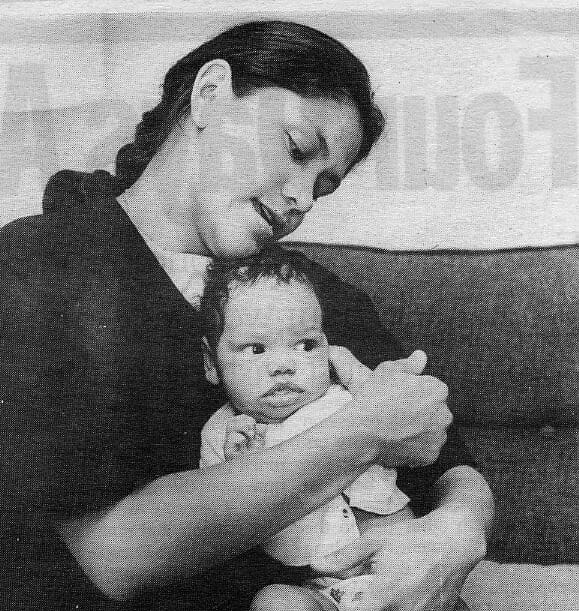

Baby Bliss: “This baby’s made everything worth it,” the ebullient Vasquez says with a smile that races toward each ear. Photo: Hillary Schalit

Now, five years later, the rest of Vasquez’s family is living in an affordable housing complex for about $100 a month. Vasquez gave birth to her son, Alex, on May 16 – less than a month before she graduated – and she plans to marry boyfriend Alexander Ukanwa in September. This fall, she’ll start Stanford’s five-quarter electrical engineering master’s degree program on a National Science Fellowship.

“This baby’s made everything worth it,” the ebullient Vasquez says with a smile that races toward each ear. “He went through a lot of lectures, a lot of all-nighters, a lot of problem sets while he was inside me.”

Born in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, near the Texas border, Vasquez moved to the United States with her migrant farmworker family at age 2. She learned English in kindergarten.

Her mother’s strong will stands out in Vasquez’s memory as much as the image of her tolling in the onion fields. “She wasn’t going to give up, she was so relentless in a quiet way,” Vasquez recalls as she sits at the kitchen table of her on-campus apartment. “She said it through her mannerisms, her humility. She disciplined us in a way where she didn’t have to hit us. She provided as much as she could for us, and we knew she couldn’t give us a lot of things so we never demanded that she buy us stuff.”

As a child in a migrant family, Vasquez barely stayed long enough at any of her schools to make friends or leave an impression on her teachers, few of whom were Hispanic. “It’s hard to see where you’re going if you don’t have role models within your own community,” she says.

Her mother was divorced and stayed single until Vasquez was about 11. When she remarried, the family eventually settled in the agricultural town of Oxnard, near Los Angeles. Their house, only slightly bigger than a standard freshman dorm room at Stanford, had just enough room for two beds. The family had no refrigerator. The bottom of their junky car scraped the ground. Vasquez, her sister and her four step-siblings spent most of their time outside since they couldn’t fit comfortably indoors.

Her authoritative stepfather ran a tight household and didn’t let her go to movies or football games with friends. Vasquez kept the worlds of school and home separate.

“I didn’t communicate anything from my private life into school, just to my best friend,” she says. “Being poor and having a family that doesn’t speak English and living in a little ugly house was something to be embarrassed about.”

When her parents missed a few months’ rent, they were told to get out in five days. They considered pursuing field work in Stockton, but they didn’t have money for gas or food.

A social worker sent them to Zoe Christian Center, a family homeless shelter about a half-mile down the street. At the center, curfews were rigidly enforced, residents had to take each other’s messages through a public phone in the lobby and the donated food sometimes made Vasquez ill.

But not only did the family gain a room twice as spacious as their previous one, they found something intangible. “We could live a little more like normal people, where you don’t have to worry about, oh my God, will we make enough money to pay the utilities, the rent? It was a little bit more stable, which is kind of strange to call a shelter, but the situation we were in before was so much worse.”

A calculus whiz who was active in community service, Vasquez applied to Stanford only because her best friend applied; she didn’t have a counselor to reassure her that she stood a good chance of getting in. She was shocked when she saw the thick envelope and generous financial aid package.

After Vasquez’s story hit the airwaves, people lavished her with praise. “No one had ever told me that I had been an inspiration,” she says. “It was really hard to think of myself as an inspiration!”

She was also showered with goods. When a Los Angeles Times article described her as wearing flashy L.A. Gear shoes, the shoe company deluged her with its products. “They sent me five pairs of L.A. Gear shoes, five L.A. Gear watches, L.A. Gear socks, L.A. Gear shorts, this little L.A. Gear jacket, L.A. Gear jeans,” she says with an incredulous chuckle.

That year, she indulged in the typically varied freshman experience. She basked in her nine months at Ujamaa, the African American themed dorm, although she notes that it was louder than the shelter. She went to parties, ate more pizza than she ever wants to see again, tutored a child from East Palo Alto, studied hard and joined engineering societies for Latinos and women.

The following summer she got a research position with California Rural Legal Assistance to research pesticide use on Oxnard strawberry fields, where workers were complaining of rashes and watery eyes. Last year, she spent six months in Paris, taking classes like French sculpture in a modern-art museum.

During spring quarter, her second physics midterm was scheduled on May 10 – the day the baby was due. She arranged to take the test a day early. Later, with two tests down – the midterm and the birth – she left the hospital, baby in tow, to study for finals, which she completed successfully.

Since then, the baby’s been sapping her energy. But Ukanwa, who she met about a year and a half ago in an electrical engineering class, is a dream father: Vasquez hasn’t had to make the baby formula once.

In the future, she says, she not only hopes to help her family with the wages from a high-tech job but also to focus her attention on her entire community.

“Coming here I realized the impact I could have,” Vasquez says. “Before, I couldn’t see to the sides. I could just see what I needed to survive.”