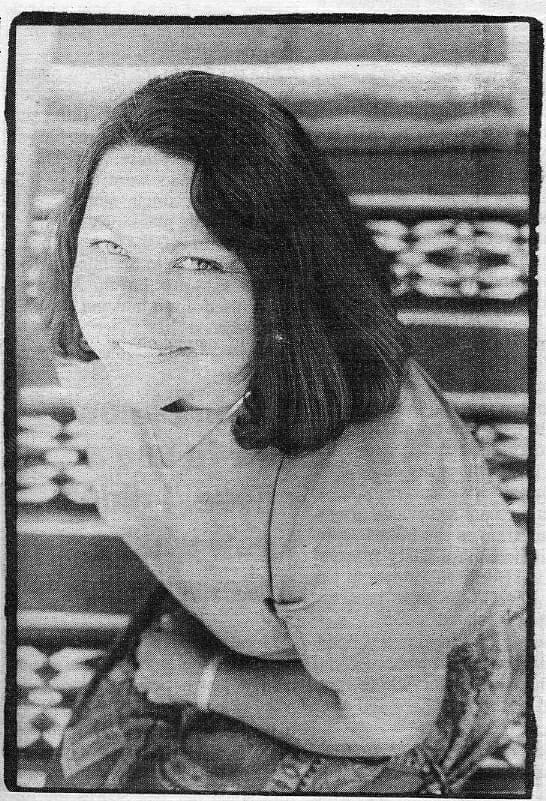

As Laverne Morrissey recounts the parable that convinced her to work as an alcohol counselor at the American Indian Center of Santa Clara Valley in 1975, the quiet strength that has made her a foundation in her community shines through.

With a gently repetitive style, she tells of a spiritual man saying prayers on a mountain at dusk. The man was enveloped by a cloud of darkness, loneliness and pain, and when the veil of pain retreated, he could see American Indians laying side by side in circles on the hillsides.

“Seeing the people around him, he started crying,” says Morrissey, who then pauses a few seconds. She looks down and pardons herself, her eyes watering. “He thought at that time that was basically the sign that it was going to be the end of our people.”

But just then, she says, one of the Indians on the hillside stood up, shook his head around and looked at the prone comrade next to him. Morrissey, sinuously acting out the gesture she describes, says that the Indian reached down and picked up his friend.

As the Indians on the hillsides picked each other up, the spiritual man on the mountain understood that all Native Americans would have to do the same to ensure their survival.

“That’s how I realized, yes, that alcoholism has been destroying our people,” Morrissey asserts softly. “If we as individuals don’t stand up and start helping in some small way, then we will no longer be.”

This story of regeneration can also serve as a metaphor for Morrissey’s work healing rifts in Santa Clara County’s 15,000-member American Indian community. With her modest demeanor, she’s helped quell long-burning personal and tribal conflicts among the American Indian Center, the Indian Health Center of Santa Clara Valley and the Muwekma Costanoan/Ohlone tribe.

A county drug and alcohol counselor since 1977, she invests her off-hours time into the American Indian Alliance, one of four programs operated by Community Partnerships of Santa Clara County. Together they’re planning to create a thriving cultural center, which Morrissey describes as a “safe haven from negativity” for the 21st century.

Nolan Grayson, executive director of the American Indian Center since last year, calls Morrissey a meticulous organizer and non-judgmental mediator who has bridged chasms.

“We have a lot more participation in our center now,” he says. “People are saying, ‘Let’s leave it, let it go, leave bygones be bygones.'”

Andrea Schneider, Community Partnerships’ executive director, describes Morrissey as a diplomat who has quietly helped heal the community’s pain through her fair questions and attentive style.

“Leadership emerges as needed in the American Indian community and sort of backs on,” Schneider says. “She’s a part of the steady corps of leaders. Now, some American Indian people that haven’t talked in ten years are working together on projects.”

Morrissey, whose shy outer shell gave way to a wellspring of emotions in a recent interview, gradually opened up as she talked about her childhood on a dusty reservation of 250 Northern Paiutes in Urington, Nev. On the “rez,” most everybody was related.

“Growing up there, every home was always open, so wherever you were hungry that’s where you stopped and that’s where you ate,” she says.

Raised largely by her mother, Morrissey always served as the referee, listener and supporting shoulder for her six brothers and one sister.

Morrissey, who grew up with an outdoor toilet and lived with the family in a 24-foot by 12-foot shack, encountered racism early on. When she severely injured her foot in a river at age 6, the family was shunned at the local hospital and was forced to drive another 25 miles to the Indian hospital.

An inveterate storyteller, Morrissey used to dream of being a writer. But in seventh grade, she wrote a story for English class that starred her family in a kind of outer-space Robinson Crusoe adventure. The teacher gave her paper an F.

“When I finally got up enough nerve to go up and ask him why he gave me an F, he said because I plagiarized the story. I said, ‘What does that mean?’ ‘It means you copied directly from a book.’ I said, ‘No, I didn’t, those are my words, I wrote those.’ He wouldn’t believe me. So after that I didn’t want to write any more.”

It took her years to realize she had been paid a back-handed compliment.

At 18, she moved out of the reservation to travel and was accepted at a junior college where she studied photography. When she took a test to determine eligibility for a government urban-relocation program, she was given her choice of locations.

Morrissey narrowed her choices to Washington, D.C., Colorado, New Mexico and San Jose. But the Bureau of Indian Affairs administrator told her she could choose only one. Suddenly the Dionne Warwick ditty “Do You Know The Way To San Jose?” popped into her head.

She arrived by bus in downtown San Jose with $15 in her pocket.

“I didn’t know how to use a phone. I didn’t know what a bus system was. I didn’t know what a hotel was. All of these, we didn’t have on the reservation.”

She got lost in the cement plains without her childhood mountains to rely upon. “The only thing the BIA guy said was, ‘It’s the tallest building in San Jose.’ You know, all the buildings were tall to me, coming from single stories,” she says, laughing pleasantly.

As the sun set, she wound up sitting on a bench in St. James Park, then a skid-row haven. A patrol car cruised up to her and the officers warned her she’d have to check into a hotel.

Morrissey kept walking until a guardian angel in the form of a Latino man took her under his wing. He checked her into a hotel, led her up to her room and told her how to find the BIA building the next day.

When San Jose BIA administrators spied her test scores the following morning, they told her they’d pay for her to attend a college like Stanford University or San Jose State University. But Morrissey refused, because at the time her reservation viewed college graduates as snobby elitists.

So the office found her a job as a clerk at an insurance company. But she didn’t feel at home until 1973, when she went to work as an information referral specialist at the Indian Center.

Last July, she met with more than 30 American Indians from Stanford to Gilroy to hear their visions for the community. They spoke of wanting to know, respect and be kind to every American Indian in the county, of yearning to educate themselves and others about the more than 80 tribes in the Bay Area.

“We go up and ask people in bookstores, where’s the American Indian reading? They say in History, like we’re past, we’re no longer here.”

Although Morrissey says that the county’s American Indians share a common goal of building a healthier community, she acknowledges that some people don’t believe they’ll be stronger working as one. But she’s patient.

“They have a place in the future,” she says.