DEBORAH OLSON is the end of the line.

At Sunnyvale’s C.J. Olson Cherries, her family has nurtured cherries and apricots for four generations. But Olson’s brother and sister aren’t interested in digging their hands into the farm’s soil. And Olson, 37, doesn’t have any children to take her place as manager of the 60-year-old fruit stand on El Camino Real.

The family recently had to bulldoze ten acres of its orchards to pay inheritance taxes and pave the way for a 59-home development. Eager commercial developers deluge the farm with offers almost daily. Although the stand will probably remain, Olson knows that meager or nonexistent profits will force the farm to call it quits within the next few years.

But Olson, who was born during cherry season in 1957 and never doubted that her destiny lay in cherries, doesn’t wallow in melancholy. Almost constantly during a recent interview she deepened her prominent dimples with smiles.

In a land of impersonal supermarkets, during an era of genetically engineered tomatoes, Olson is righteously making her stand. As one of the last remnants of the county’s days as “The Valley of Heart’s Delight,” she’s working hard to forestall the suburban juggernaut.

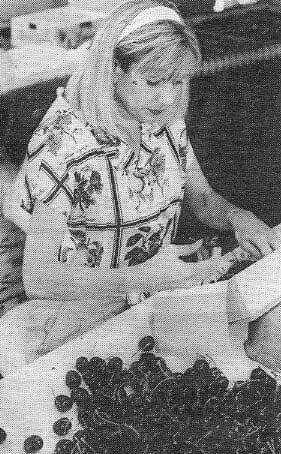

Very Cherry: Deborah Olson wears gold-outlined cherry earrings and a blouse with sketches of the fruit. Photo: Hillary Schalit

“You don’t know when that day’s gonna happen, you can’t just stop,” she says. “You have to keep planting trees, you have to still prune trees and water ’em, and always prepare for the next year, because you don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Her father, Charlie, a farmer who knows each of his trees almost as well as he knows his own children, owns the 16-acre property along with Olson’s aunt, Jeanette Gottesman. When El Camino was a bucolic two-laner, a young Olson and her family put crates of apricots and cherries on the side of the road to entice passersby. Now, cars and trucks barrel past on four lanes all day long. Office buildings and gas stations have sprouted on the farm’s periphery like weeds.

In addition to destroying the area’s orchard ambiance, the boom in asphalt has made the winters warmer. The once-plentiful trees and dirt used to absorb the sun’s heat, but now, Olson says, the change in microclimate sometimes fools the cherry trees into blossoming twice – which leads to smaller fruits.

But the hard work required to run the farm – which was named Sunnyvale Chamber of Commerce’s Small Business of the Year in 1993 – hasn’t changed over the years. To manage the fruit stand during the season, Olson usually works 12 to 15 hours a day, seven days a week, in a kind of grueling but fulfilling triathlon that ends this month.

“If I’m away for just a day or so I miss it,” she says. “I love the chaos. As long as I get enough sleep I’m okay.”

The Olsons haven’t faced any disasters this season – the apricot crop actually doubled in size from last year – but any wagers placed on nature’s future performance are shaky at best. Last year’s cherry crop was shining one Saturday morning but battered by rain Saturday night. By Sunday, Olson says they’d lost half the crop. So they made jam.

“I’ve gotten over the turmoil of it all, and the depression, because it’s nature and there’s nothing you can do,” she says. “If you go to bed and it’s raining, you wake up and pray it was a bad dream, but all of a sudden it’s still raining. It’s like, oh nooo, but what are ya’ gonna do.”

Olson sometimes talks with her mouth full because she can’t help but eat the fruit of her efforts, especially the smaller, tarter apricots. They are the product of 10 city-owned acres of apricots the Olsons also care for, a parcel of land which will be the last remaining orchard in Sunnyvale when the Olson farm is gone.

Standing beside a sea of apricot drying trays one recent weekday morning, the slim woman looked like she’d dive right into them if she could.

But it’s the crimson tide of the cherries that has washed over her heart. Every day she wears gold-outlined cherry earrings, not just for interviews. Her lipstick shade is bright cherries and she’s dressed in a blouse covered with sketches of the plump spheres.

While farmers can raise berries, peaches or nectarines all year round, Olson says cherries still retain a lot of mystery since they’re seasonal. She also rhapsodizes about their juiciness, their different hues and the complexity of flavors in varieties like Tartarians, Bings and Royal Annes.

Olson, who gulps down cherries morning to night, had never maxed out on the Vitamin C-laden fruits until this summer, when she took a walk in the orchard with one of her oldest friends and customers.

“It was just gorgeous, and the Mexican pickers were singing Mexican songs, and we were eating cherries off the tree,” recalls Olson, who cooks, scuba dives and takes ballet in her rare spare time. “I don’t know how many I ate, but I came back and I got sick to my stomach, all day. I was amazed.”

Olson’s great-grandfather started farming in San Francisco in 1899 and eventually bought five acres in Sunnyvale in 1902. Her grandmother, a native of Lebanon, started the retail stand in 1935.

Olson’s dad was sorting cherries when the call came announcing his wife had just given birth to a girl, Deborah. Starting at about age 6, Olson cut apricots from 10am to 2pm during summers. She’d also join her dad on the train as he took boxes of cherries to auctions, where they garnered high bids.

Now Olson lives across the street from the farm in her great aunt’s house, near her parents. The farm foreman lives in her great-grandparents’ house, with its roses and quaint archway. Many of the faces behind the cash register have remained the same in the last 40 or 50 years. The foreman labored for Olson’s late grandfather.

Olson, who has shuttled back and forth to Paris for culinary school during the last 12 years, tries to maintain the old-fashioned atmosphere as she eagerly calls out “good mornin'” to people walking into the stand. Once inside they poke through pyramids of melons and tomatoes and endless boxes of cherries – as their grandparents might have done 50 years ago.

“This is the way it was; I think that’s part of the charm of the place,” Olson says. “It hasn’t changed.”