After a month of constant sleep and hallucinations under 104-degree fevers earlier this year, Ernie wanted to die.

“I remember just rocking my head back and forth, and I was crying,” sobs the San Jose resident, who has AIDS. “I asked my wife Virginia if I could die. And she cried, and then she said, ‘If you’re tired, just give up, go ahead. Die, if that’s what you need to do, die. Because we understand.’

“I told her, “There’s going to be a point in my life where I have to give up. I’m not gonna be able to keep fighting it.'”

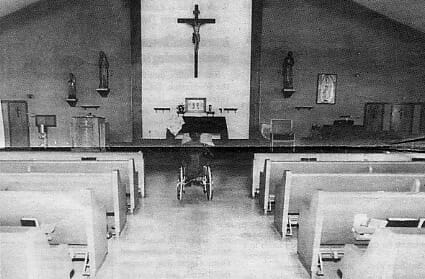

A priest performed the traditional anointing of the sick for the bedridden Ernie, a 44-year-old non-practicing Catholic. He confessed for an hour and a half.

When Father Kevin held his hands over Ernie’s head, Ernie felt a stream of warmth gush from them.

“I thought I had accepted it before that, but now I’m at peace with myself,” Ernie says. “I mean, I don’t want to die, but so be it. You die the way God wants you to go.”

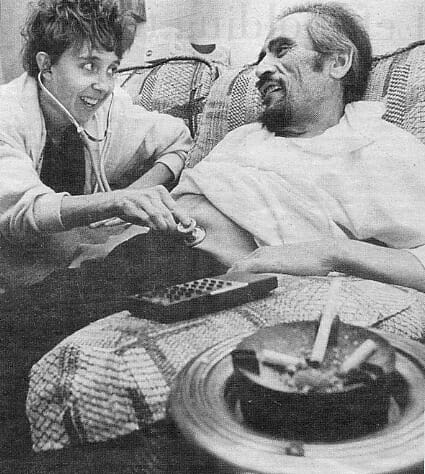

Gentle Touch: In addition to pain and symptom management -— her primary responsibilities — Julie sometimes gives Ernie a back rub.

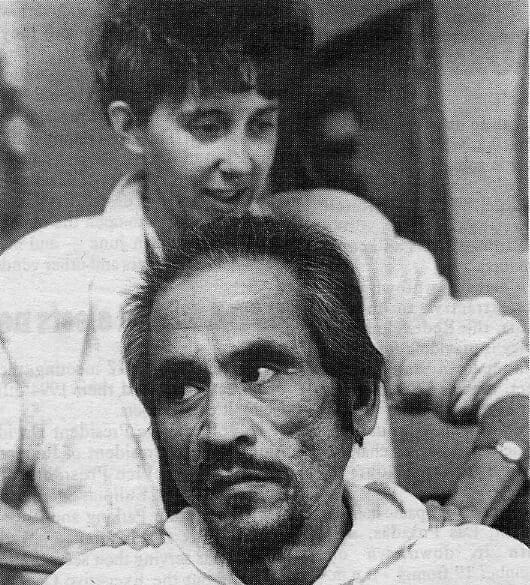

Ernie – a spiritual, rather than religious, man – prays every morning now. His graying hair is sprouting again, and he plans to grow it out like his days of old. Early one recent morning, for the first time in a year, he transplanted a flower into his beloved garden, which he can see from his living room recliner chair. He sews and cooks dinners again, often chopping the ingredients early in the day.

Ernie attributes this remarkable recovery largely to the Santa Clara Valley Visiting Nurse Association’s Hospice at Home program, whose hospice staff members entered a threatened life at just the right moment.

“They’re more my friends than they are caretakers,” he says.

Hospice worker Julie Dutton counters that Ernie has taken the reins on his own comeback. But perhaps it’s their synergy that has allowed his feisty, talkative, class-clown personality to endure since they started working together in June.

“Ernie really represents highly our focus in hospice on quality of life,” Julie says. “We like to be about living and not about dying, per se. I think Ernie’s quality of life is still pretty decent. A lot of times, people decide what quality is for them, and when that quality isn’t to the level they wanted, they start letting go. It’s kind of a spiritual process as well as physical and emotional.”

Hospice at Home seeks to ease the death and dying process for patients and their families by expanding beyond traditional hospital options. The specially trained nurses, physical therapists, home health aides and social workers offer patients like Ernie the framework they need to maintain a vibrant life.

Ernie still suffers headaches. He says the experimental drug AZT ruined his feet. He knows this plateau won’t last forever.

He used to weigh in at 207 pounds. He’s now 134, after hitting a low of 120. “It’s real hard to see what you’ve become when you know what you were,” he cries, looking at pictures from the emotional wedding vow-reaffirmation ceremony he and Virginia recently shared.

He believes pneumonia will bear the sickle for him. He made all the funeral arrangements himself — an open casket for immediate family only. He’s decided who will receive his diamond ring, his gold chains, his leather jacket.

But Ernie won’t roll over and die. “There’re just too many positive things happening to me to think negatively,” he says.

Although he eloquently addresses the somber elements of his life, an impish humor defines his personality.

During a session with Julie, Ernie jokes that she purposely chills the blood pressure cuff she uses on him, and suggests she sit on it on the way over to warm it.

She places a stethoscope on his stomach, covering scars from previous surgery. “You didn’t know your heart was down there?” she needles him.

As she’s kneading his back, he winces when she touches one tender area. He savors the tactile attention on his biceps.

“Oooh, that feels good. No one’s ever done that to me before,” he says, then turns and smiles mischievously.

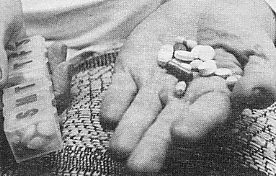

After pretending to wheeze as she listens to his lungs (he says smoking is his only vice), Ernie opens his mouth wide for a thermometer – 98.5 degrees. Later, he proffers the multicolored assortment of 14 pills he has to swallow twice a day.

Julie looks tired on this day; she was up from 2-5a.m. on call. She sees six patients one to three times a week – cancer patients, or elderly people damned with a “failure to thrive.” But Ernie? When she kisses him goodbye on the forehead, this joker who sings in the supermarket complains about “cooties.”

“Ernie is a fighter, but he’s also very realistic and in touch with how he’s feeling,” Julie says.”Some days, he’s just not feeling so good.”

He doesn’t hesitate to express what’s going on inside. Once, he pushed over a Mervyn’s clothing rack to protest the difficulty of maneuvering his shiny new wheelchair through the racks. He admits to this reporter he’s been feeling him out to see if he likes him.

“I consider Ernie a personal friend – except he won’t ever loan me any money,” says hospice worker Don Ruebenson, a gentle bear of a man who helps Ernie shower and massages his numb toes with cream during his thrice-weekly visits.

“He bitches at me, he yells at me, but it’s only the truth, which I really, really appreciate,” Ernie says, sitting in a living room filled with Native American decorations. But he smirks that he won’t let Don “overstep his bounds” and later suggests that the surgical mask Don sometimes wears ought to cover his entire face.

When the phone rings, Don shoots back. “Virginia’s calling, so he’s getting the sympathy – ‘Oh, honey, I feel so bad.'”

Ernie and Virginia share a passionate, vibrant love.

“I think about her so much – the hell I’ve been putting her through,” Ernie says, deep worry lines furrowing between his eyebrows. “She never complains. She always tells me, I’m going to take care of you.”

As a poor student 21 years ago, he asked the well-off Virginia to marry him, only 2 1/2 months after he met her at San Jose City College.

They couldn’t have kids together, so they raised nine neighborhood boys. Hector, who cuts his lawn, snared a master’s at UC-Berkeley. Abel manages a muffler shop, while some others have become involved with drugs.

Ernie told them all, “If you ever run across somebody that needs help, help them – because that’s what happened to me.”

He suffered a nervous breakdown when cherished “son” Curtis died a few years ago at age 17. “I talk to him still. I say, ‘Well, pretty soon I’ll be with you,’ and my wife prays to him, ‘Don’t take him. He’s not ready to go.'”

Serene Silence: Ernie spends a peaceful moment before renewing his wedding vows with his wife of 21 years. He says he has rediscovered his faith since he became ill and says his priest has helped him maintain a positive mental state.

Ernie relates a haunting experience: A week after seeing Curtis’ spirit standing at the door, Ernie turned to a random page in the Bible. The passage read, “I am leaving now, Israel shall take my place.” The next boy he took in was named Israel.

Such spiritual thoughts touch Ernie’s mind often these days. His mom died when he was 2 years old, leaving behind no pictures, and Ernie says, “That’s the first person I want to meet if I die and go to heaven.”

His hardworking but emotionally abusive farmworker dad, who died in 1990, gave him away to an aunt. The only one in his family to graduate from high school and get a college education, he worked for the telephone company.

The only survivor of six in a Highway 17 car crash – which burdened him with epilepsy – he thinks he got HIV during three major surgeries within 14 months in the late 80s. “But it doesn’t matter how I got AIDS – I’ve got it.”

At first, half his family wouldn’t talk to him when they learned he was HIV-positive, because they didn’t know how to act. His little brother refused to see him.

“He’d go as far as my driveway and drop off the food I had wanted but wouldn’t come in,” Ernie says, the pain evident on his face.

But one day his brother walked in, and – reconciled – “We … cried … like … hell.”

When Ernie got full-blown AIDS in May, doctors forecast he would die in December. But he’s looking inward and projecting love and humor outward at full steam.

“I know this is going to kill me, but I also know I could walk outside and a tree could fall and hit me,” he says. “There’s really nothing you can do about it. I don’t even care if I die, if they could only find a cure for AIDS.”